1 Introduction

After I have already written some posts about different SQL functions I would like to write a structure-bringing publication at this point again.

In the following I will explain the different SQL command types:

- Data Definition Language (DDL)

- Data Query Language (DQL)

- Data Manipulation Language (DML)

- Data Control Language (DCL)

- Transaction Control Language (TCL)

2 Types of SQL Commands

2.1 Data Definition Language (DDL)

DDL describes the SQL commands that can be used to define a database schema. They are mostly used for creating and changing the structure of database objects in the database.

Examples of DDL commands:

2.2 Data Query Language (DQL)

DQL statements are used to query data within schema objects.

An example of this would be:

- SELECT - retrieve data from the database

2.3 Data Manipulation Language (DML)

The commands from this category deal with the manipulation of the data inside the database.

Examples of DML commands:

2.4 Data Control Language (DCL)

DCL commands mainly deal with the permissions and other controls of the database system.

Examples of DCL commands:

2.5 Transaction Control Language (TCL)

I want to go into a little more detail on this section, since I haven’t covered it in any other post of mine.

Transactions bundles a group of tasks together into a single unit of execution. Each transaction starts with a specific task and ends when all tasks in the group complete successfully. If any of the tasks fail, the transaction fails. Therefore, a transaction has only two outcomes: Success or failure.

Transactions have the following four standard properties, usually referred to by the acronym ACID.

- Atomicity − ensures that all operations within the work unit are completed successfully. Otherwise, the transaction is aborted at the point of failure and all the previous operations are rolled back to their former state.

- Consistency − ensures that the database properly changes states upon a successfully committed transaction.

- Isolation − enables transactions to operate independently of and transparent to each other.

- Durability − ensures that the result or effect of a committed transaction persists in case of a system failure

Transaction Control

I will use the following commands to control transactions:

- COMMIT − to save the changes

- ROLLBACK − to roll back the changes

2.5.1 Preparation

For the following examples, I set up a new database.

SET LANGUAGE ENGLISH

CREATE DATABASE SQL_Types;

USE SQL_Types;Now I will quickly create a simple example data set:

CREATE TABLE Employees

(Employee_ID INT NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY,

Job_Titel VARCHAR(100),

Name VARCHAR(100) NOT NULL,

Age INT NOT NULL)

;

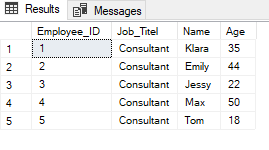

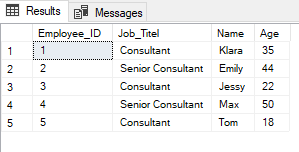

INSERT INTO Employees VALUES (1, 'Consultant', 'Klara', 35)

INSERT INTO Employees VALUES (2, 'Consultant', 'Emily', 44)

INSERT INTO Employees VALUES (3, 'Consultant', 'Jessy', 22)

INSERT INTO Employees VALUES (4, 'Consultant', 'Max', 50)

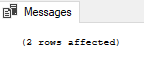

INSERT INTO Employees VALUES (5, 'Consultant', 'Tom', 18)SELECT * FROM Employees;

2.5.2 Update a Table

Let’s say I want to change the contents of a table for certain people, for example the job title. We can do that as follows:

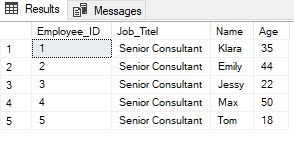

UPDATE Employees

SET Job_Titel = 'Senior Consultant'

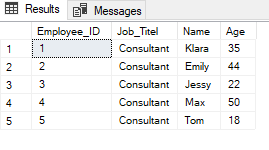

;SELECT * FROM Employees;

Oops. Now I have accidentally changed the content of the column for all persons. With such an error I can destroy the complete table.

Therefore, I will have to set it up again.

2.5.3 TRANSACTIONS

To prevent such an error, I can use Transactions.

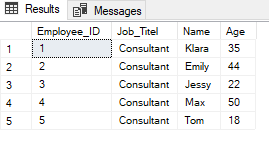

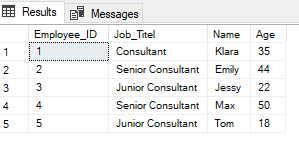

Here again the original table that I restored:

SELECT * FROM Employees;

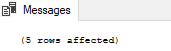

I can initiate a transcation with the following command. At the same time I use ROLLBACK so that it is not executed.

BEGIN TRANSACTION Change_Title

UPDATE Employees

SET Job_Titel = 'Senior Consultant'

ROLLBACK TRANSACTION Change_Title

;

I see here in the output that 5 lines would be affected. At this point I would notice that something is wrong with my command.

I forgot to use a WHERE statement to narrow down the group of people.

BEGIN TRANSACTION Change_Title

UPDATE Employees

SET Job_Titel = 'Senior Consultant'

WHERE Age > 40

ROLLBACK TRANSACTION Change_Title

;

Perfect. This statement is now correct.

But so far my table has not changed, see here:

SELECT * FROM Employees;

2.5.3.1 COMMIT TRANSACTION

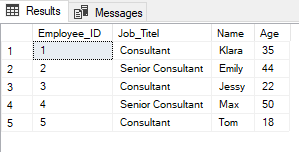

Now that I have validated that my statement is correct using the Transaction commands shown earlier, I can perform the transaction. This can be done with the COMMIT command.

BEGIN TRANSACTION Change_Title

UPDATE Employees

SET Job_Titel = 'Senior Consultant'

WHERE Age > 40

COMMIT TRANSACTION Change_Title

;SELECT * FROM Employees;

Now the title of the correct group of people has been changed.

2.5.3.2 ROLLBACKS

However, TCL offers other useful functions to be able to validate a transaction. The so-called ROLLBACKS. With this I have the possibility to reset the previously made transaction if I notice that it was not quite correct.

This becomes clear in the following example. I would like to change the title of certain persons again. This time I use the following commands:

BEGIN TRANSACTION Change_Title_2

BEGIN TRY

UPDATE Employees

SET Job_Titel = 'Junior Consultant'

WHERE Age < 25

END TRY

BEGIN CATCH

ROLLBACK TRANSACTION Change_Title_2

END CATCH

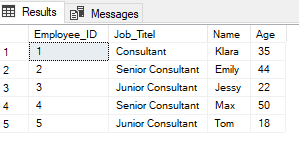

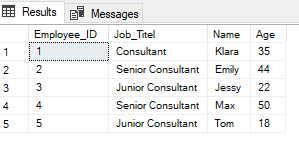

;Here I have instructed a transaction with the desired changes but have not yet used a COMMIT. But the changes are already visible in the table:

SELECT * FROM Employees;

If I realize at this point that I have made a mistake, I can reverse the transaction:

ROLLBACK TRANSACTION Change_Title_2;SELECT * FROM Employees;

We see, I get my old table back.

I now run the same transaction again and then use the COMMIT command:

BEGIN TRANSACTION Change_Title_2

BEGIN TRY

UPDATE Employees

SET Job_Titel = 'Junior Consultant'

WHERE Age < 25

END TRY

BEGIN CATCH

ROLLBACK TRANSACTION Change_Title_2

END CATCH

;SELECT * FROM Employees;

We see the table has changed again as before. And this time i use COMMIT:

COMMIT TRANSACTION Change_Title_2;Now the transaction is through and cannot be changed:

SELECT * FROM Employees;

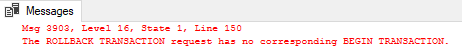

Even if I tried a ROLLBACK now, it would fail:

ROLLBACK TRANSACTION Change_Title_2;

2.5.3.3 SAVEPOINTS

A topic that I will not present now as an example but I also did not want to withhold from you are SAVEPOINTS.

These can be set at different places within the grouped tasks of a transaction to which one can jump back with the help of a ROLLBACK. In this way one avoids that the complete transaction has to be executed again, but prevents in the same step that erroneous task packages are taken over.